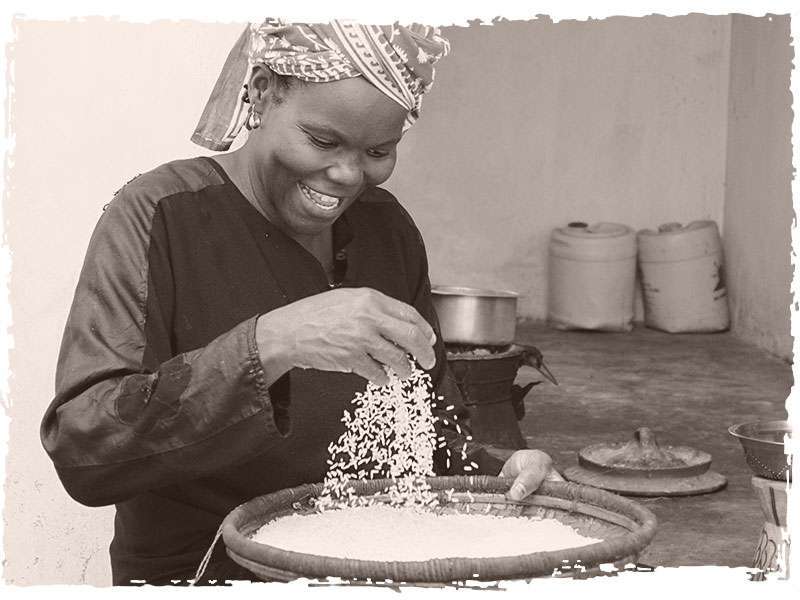

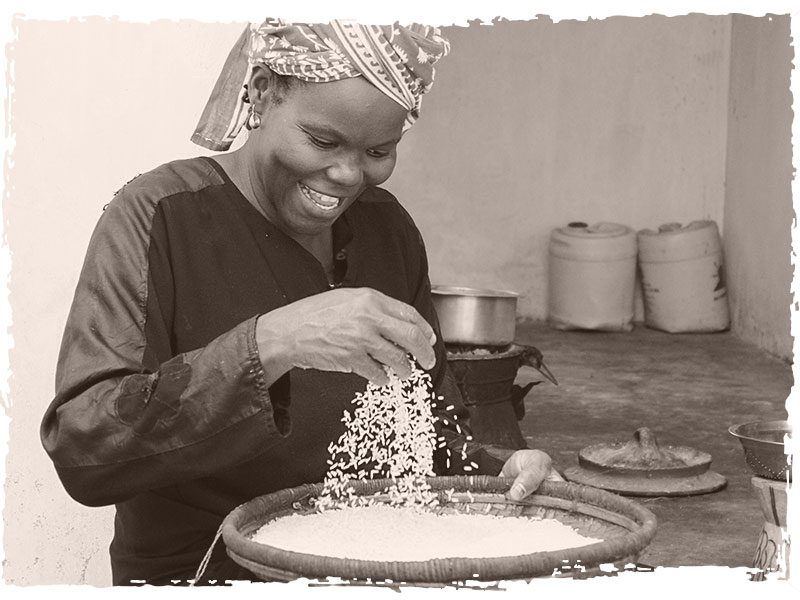

n 2014 I was asked by a friend in Tanzania to speak to a group of vulnerable young men and women. Their backgrounds were ones of poverty, abandonment, and unemployment. I asked my friend whether sexual abuse was in the mix for them as well. In my home country of Australia, they say one in five women have experienced sexual abuse. UN Women suggests it is about double in Tanzania.[1] My friend told me that at a gathering of university students in Kenya they had asked the girls to raise their hand if they had experienced sexual assault. He was staggered that 80 percent raised their hands.

In 2014 I was asked by a friend in Tanzania to speak to a group of vulnerable young men and women. Their backgrounds were ones of poverty, abandonment, and unemployment. I asked my friend whether sexual abuse was in the mix for them as well. In my home country of Australia, they say one in five women have experienced sexual abuse. UN Women suggests it is about double in Tanzania.[1] My friend told me that at a gathering of university students in Kenya they had asked the girls to raise their hand if they had experienced sexual assault. He was staggered that 80 percent raised their hands.

Global problem

There are some technicalities around the differences between sexual harassment, assault, and abuse which may be part of what skews the statistics, but these are matters of degree. Harassment, assault, and abuse are part of the same package whereby women are vulnerable and preyed upon by men in societies around the world. #metoo is a Twitter hashtag which has gone viral, giving a sense of the magnitude of the problem of sexual harassment and abuse:[2]

#metoo

Used in 85 countries

Suggests Western women’s

experience mirrors Kenyan

and Tanzanian

- The hashtag, used in 85 countries,[3] has brought to light thousands of stories from the US entertainment industry to politics to sport to waitressing.[4]

- Although it has been less popular in Africa, the #metoo movement suggests that Western women’s experience mirrors that of their Kenyan and Tanzanian sisters.[5]

A spinoff hashtag, #churchtoo, saw women and girls share their experiences of similar harassment and abuse in the church.[6] They spoke of being blamed, disbelieved, discouraged from going to police, and made to apologise for the sexual assault they received. Furthermore, there were stories of perpetrators who stood up and apologised publicly for their behaviour, with no further consequences. The abuse of women is not just an issue in society at large. It is an issue for the church as well.

Other types of abuse that women experience globally include Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), forced prostitution, slavery,[7] child marriage, and domestic and family violence (DFV).

Equality

In this global climate where women are vulnerable and it is a normal experience for them to be abused, a prevailing strategy for addressing this has been to argue for the equality of women as key to raising them up. This has been the case in the church too. Groups like Christians for Biblical Equality[8] have the word in their name. It has become shorthand for Jesus’ treatment of women too, as in Nicky Gumbel’s tweet from February 2018[9] which equates liberation and affirmation of women with being treated as equal to men.

However, the meaning of ‘equality’ may not be consistent across cultures. For example, Tanzanian women affirm equality but are much more comfortable with hierarchy than me:

- To an Australian with in-built egalitarian ideals, hierarchy seems opposed to equality, as a system that inevitably oppresses those at the bottom. My cultural instinct is to dismantle and flatten hierarchies.

- Although Tanzanian women acknowledge, experience, and grieve over abuse of women, many insist that abuse comes from the misuse of hierarchy rather than being inherent in hierarchy itself.[10] In their view, hierarchy does not necessarily threaten equality.

Attempts to see this cultural understanding rejected as unbiblical must wrestle with James’ assumption that there will be economic inequality in the church, and Paul’s nuanced use of ‘equality’ in 2 Corinthians 8:13-15 where his emphasis is on the needs of poverty-stricken Christians being met in friendship.[11]

Imago Dei

With equality a vexed concept in a global world, a more fruitful way to shape our response to abuse of women is with the Imago Dei, or the image of God.

In Genesis 1:27, humankind is created in God’s image:

‘So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them’ (NIV).

Together male and female image God; they are like him and bring glory to him. If one part of this partnership is diminished, humanity is impoverished, and the glory of God is tarnished. Abuse of God’s images is insulting to their Creator. The doctrine of Imago Dei locates women’s dignity not so much in their status in relation to men (their ‘equality’, or lack thereof), but in their imaging of the Creator. It is because of who God is that women ought to be afforded their full dignity. From a Christian perspective, addressing the abuse of women has a fundamentally theocentric reason: to mistreat those he loves is to grieve the Creator; to deface his image is to tarnish his glory.

THE DOCTRINE OF IMAGO DEI LOCATES WOMEN’S DIGNITY NOT SO MUCH IN THEIR STATUS IN RELATION TO MEN (THEIR ‘EQUALITY’, OR LACK THEREOF), BUT IN THEIR IMAGING OF THE CREATOR.

While equality cannot appeal to both hierarchical and less hierarchical cultures, the Imago Dei provides the currency for both to honour women. When Jesus heals and affirms the woman bent double in Luke 13, he speaks of her as a daughter of Abraham whom Satan has bound. That is, he speaks of her as a part of God’s family and an inheritor of God’s promises, without reference to her standing in comparison with men. What is on view is this woman’s dignity. Irrespective of our cultural views of hierarchy, we can be united with Jesus in caring for her and seeing her restored. One ministry to women university students in Tanzania is called ‘Soaring Women’, which encapsulates this idea. The doctrine of the Imago Dei gives us a biblical language that can unite us across cultures to pursue the flourishing of women.

What next?

In the Imago Dei, Christians have the theological resources to pursue the flourishing of women. What practical resources could we avail ourselves of to help us live out and apply this doctrine to the abuse of women? If Christian leaders are to pursue a restoration of women’s dignity, they will need to dismantle several obstacles, and undertake a process of education, restitution, and restructuring. Here are three suggestions:

1. Train pastors better about what abuse is, how to recognise an abuser, and how to respond to the abused.

Pastors without categories of abuse (physical, emotional, financial, verbal, spiritual, sexual) may struggle to identify why a man who does not beat his wife but constantly belittles her and controls all their money is abusive. Without an adequate understanding of grooming, a pastor may find it hard to believe that a man who seems so charming and godly at church could be the abuser his wife describes. Pastors may be tempted to blame the victim for the abuse, asking her how she provoked it, or telling her to act or dress differently in the future, thereby placing the responsibility on her rather than squarely where it belongs: on the abuser. ‘Safer’ is a good resource from Australia.[12]

2. Include more women in Christian leadership, including staff teams.

Whether from theological conviction or happenstance, Christian leadership is male dominated. This means that male perspectives are preferenced in institutional structures and theology,[13] and they can be quick to assert #notallmen[14] or slow to listen to women because they find offensive the forthrightness with which women have brought it to their attention.[15] The solution must be to hear more from women, that male leaders may broaden their perspective and gain greater empathy.

I suggest that every Christian staff team ensures that it has at least two women on it. One woman is easily dismissed, and with women’s voices generally being considered less authoritative than men’s, it takes more of them speaking for them to be heard.[16] Having multiple women guards against making one woman’s experience universal and allows us to see the shades in women’s experiences and perspectives. Finally, being the lone woman on a staff team can be very isolating. The two or more women can offer support to one another as well as amplifying one another’s voices.[17]

3. Seek restitution and reconstruction.

Every organisation will have women it has failed. Consider a process of some years, identifying, listening to these women, and asking them what they want to change. Make public apologies, ask them what they want you to do, and do it, even if it means a loss of status or face for you or their abuser. Do not engage in cover-ups, deal with issues ‘quietly’, or sweep allegations under the carpet, never to be dealt with.[18] Put into place line management and grievance procedures. Bring in women from outside to consult with you on the culture of your staff team and your church or organisation. Pay them well, and accept their findings and action points.

WHEN UNBELIEVERS LOOK AT THE CHURCH, IF THEY ARE TO SEE CHRIST WITH ANY CLARITY, THEY MUST SEE WOMEN FLOURISHING.

An American atheist friend of mine remarked that he was surprised that I would consider Christianity a source of life and flourishing for women, since in his view Christianity has been a source of oppression of women. His comments brought home to me that our ability to deal with the abuse of women in the church has an element of witness to it as well. If we say we are without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us (1 John 1:8); so we must pursue the One who can purify us from all unrighteousness and eagerly take the opportunities we are presented with to make things right. When unbelievers look at the church, if they are to see Christ with any clarity, they must see women flourishing.